1 Modelling Fires

The motivation for this chapter is to provide an overview of the involved phenomena and methods in the modelling of fires. In the first section a brief summary of the physical and chemical processes is given. As one of the application scenarios for fire simulations is fire safety engineering (FSE), the second section outlines some selected aspects of this field of engineering – especially for those who are not familiar with it.

There exist multiple ways to model fires, although this lecutre focuses on field models, i.e. computational fluid dynamics models. In the third section an overview of existing modelling approaches is briefly outlined.

1.1 Physical and Chemical Processes

1.1.1 What is a Fire?

In general: A fire is an exothermic chemical reaction.

Technical Combustion – Wanted Fires

Wanted fires, i.e. technical combustion processes, are controlled processes used for e.g. heating or propulsion. Although the term wanted fire is somehow misleading, as the fires are typically not wanted and associated with accidents, a bonfire is one of the fundamental wanted applications of fires.

Unwanted Fires

Unwanted fires, are not controlled and not wanted processes. These are mostly incidents inside of enclosures and pose danger to wildlife, humans, and property.

Fire Examples

- Bonfire

- Wildland fires

- Compartment fires

1.1.2 Processes Overview

Fires involve a complex interaction of a multitude of physical and chemical processes. While most of them take place in the gas phase, e.g. combustion, fires commonly include also processes in the solid or liquid phase, e.g. pyrolysis which generates the fuel for the combustion. The following processes cover the main phenomena.

- Fluid dynamics

- fundamental mass and momentum transport process in the gas phase

- fire related flows are mostly turbulent

- Heat transfer

- warm gas, e.g. combustion products, are transported upwards by heat convection

- hot matter emits net thermal radiation

- heat conduction inside the solid

- Combustion

- fast oxidation of fuel in the flame

- release of chemical energy, e.g. locally heating gas or thermal radiation

- Pyrolysis

- degradation of the solid structure

- emission of volatile gases, e.g. fuel for the combustion

1.1.3 Fluid Dynamics

Fires induce heat in the gas phase and buoyancy of the heated gas drives a plume. Compartment flows are complex and involve many openings to ambient regions as well as obstructions, see Figure 1.4. Mechanical ventilation, systems for heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) as well as wind might be included into the evaluation of the dynamics.

Most fire flows, especially in the flame and plume region, are turbulent. The turbulent mixture process during combustion is crucial and the entrainment of fresh cold air into a plume significantly determines its dynamics. Experimental analysis as well as numerical models must consider the macroscopic effects of turbulence.

1.1.4 Reactive Flows

Fires are driven by the energy released by combustion, which is an exothermal chemical process. In the simplest case, two gas species, here oxygen and fuel, react and release energy. In real fires, there is a zoo of species and reactions involved. Depending on the concentrations of individual species and their local temperatures, new chemical species can be formed. Thus, the overall spectrum of products, due to the chemical processes during a fire, is rarely simple.

In contrast to technical combustion, in fires the oxygen and the fuel are typically not mixed. The transition from a non-premixed to a premixed combustion can be well observed with a Bunsen burner, see Figure 1.6.

The time scales at which the chemical reactions take place span multiple orders of magnitude, see Figure 1.7. Typical combustion processes are much faster than common mass transport processes in fires.

1.2 Heat Transfer

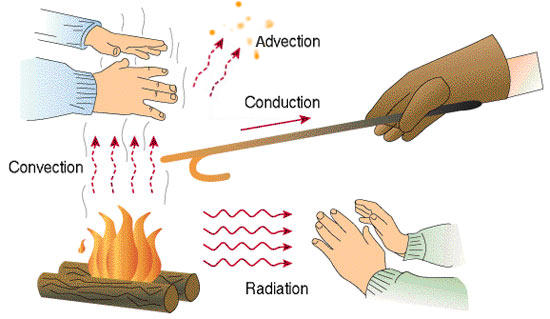

Heat can be transferred between locations and materials in different ways. The flow of heat is driven by differences in temperature. There are three modes to transfer heat, where only conduction and radiation are fundamental and do not require a fluid in a gravity field.

The heat transfer modes are:

- Convection: transport of matter with different temperatures due to induced buoyant flows

- Conduction: diffusion of heat in a material

- Radiation: emission and absorption of electro-magnetic waves

All three modes are important for fires. The released chemical energy from combustion locally heats up the gas, which changes its density and is thus affected by buoyancy. Beside the local heating, the hot gas emits thermal radiation in all directions. Thus, in case of a compartment fire, it transfers heat towards the walls or other structures, and e.g. towards the solid, which provides the fuel source for the fire. Thus, the solid’s surface heats up and heat conduction spreads the absorbed energy through the solid.

1.3 Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis describes the emission of (potentially combustible) gases out of solid material. In general, this is dependent on the solid’s temperature as the decomposition reactions require energy. For liquids, additional evaporation can take place.

In case of burning wood, like a match in Figure 1.9, the solid material itself is not part of the combustion, but delivers only the fuel for the fire. Not all material is gasified and a char residue is left.